Physics Simulation Based Algorithms for Space-Efficient 2D Packing in Additive Manufacturing

Table of Contents

Overview

This is a course project for CS 530 Advanced Algorithms, Fall 2025. The goal is to survey algorithms for 2D irregular packing and implement a new algorithm based on what I learned in this course and recent research.

Although I previously worked on the “Fill the Build” feature at Formlabs, this project is independent of that work. The algorithm presented here is my own implementation and does not use any proprietary code or internal knowledge from Formlabs.

Abstract

This project aims to explore approximation algorithms and heuristics for space-efficient 2D packing in additive manufacturing. We will investigate various algorithms and heuristics to optimize the arrangement of objects within a given volume, minimizing wasted space and improving packing efficiency. In the end, I implemented a prototype algorithm and evaluated its performance on various test cases.

Introduction

Additive manufacturing, commonly known as 3D printing, has transformed how complex objects are designed and produced. From rapid prototyping to small-scale manufacturing, it enables the creation of customized, complicated geometries that are impossible to manufacture using traditional methods. However, despite these advantages, one of the biggest bottlenecks preventing the adoption of large-scale additive manufacturing is the inefficient use of build volume. Each print job typically requires significant pre-print and post-print steps, including preparation, material loading, heat-up, machine cool-down, finished part removal, and cleaning. These steps have a fixed time overhead and are independent of the number or total volume of printed parts. Consequently, maximizing the number of parts packed within a single build is essential to improving throughput and reducing production cost.

The most common 3D printing technologies, such as Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) and Stereolithography (SLA), build objects directly on the build plate layer by layer. SLA printers use a laser or projector to cure liquid resin into solid layers, while FDM printers extrude melted thermoplastic filament layer by layer to build the object. I had the privilege to work on the software teams of both Formlabs and Bambu Lab, two leading companies in SLA and FDM technologies, respectively. This gives me a solid foundation in understanding the practical challenges and real-world constraints of additive manufacturing.

For FDM and SLA, the models will be put on a flat, rectangular build plate, which means the model will be placed on the XY plane. Models typically cannot build on top of each other, as this would impact the quality of the print and may lead to print failures. Therefore, the problem of maximizing the number of parts printed in a single job reduces to efficiently packing the 2D projections of the objects onto the build plate.

This can be formalized as a two-dimensional packing problem: given a fixed rectangular build plate and one or more objects with known geometries, the task is to arrange and orient these objects to print as many copies as possible while preventing overlap.

Traditionally, bin packing problems involve packing a set of different-sized items into fixed-size bins in a way that minimizes the number of bins used. The traditional bin packing problem, in both one and multiple dimensions, is known to be NP-hard (Korte and Vygen 2006), and thus exact optimal solution is computationally infeasible for real-world usage. This motivates the use of approximation algorithms, which aim to produce near-optimal solutions in polynomial time.

In the context of additive manufacturing, the geometry of the objects being packed can be arbitrary and is often concave. Furthermore, a feasible packing algorithm must also respect domain-specific constraints: objects require a minimum clearance to prevent fusion during printing, and users may want to print the object in a fixed orientation to maximize the mechanical strength. These additional restrictions make the 2D packing problem more challenging, yet they are crucial for practical applications in 3D printing.

I had past experience working on packing algorithms for 3D printing software at Formlabs. I worked on the “Fill the Build” feature for SLA. The feature works as follows: after the user selects one or more models to duplicate, the algorithm will try to pack as many copies of the models on the build plate as possible. In Figure 2, the left side “Layout” panel shows the parameters the user can set for packing, including spacing between models, spacing from the edge of the build plate, allowing the support structures to touch, and locking rotation or not. The right side shows the result of duplicating a concave model multiple times and packing them on the build plate. The packing process completes within seconds for this example.

This project aims to bridge algorithmic theory and practical application by studying approximation algorithms for 2D bin packing under additive manufacturing constraints. To meet the real-world needs of 3D printing users, the focus will be on developing an algorithm that runs in a reasonable time while achieving acceptable packing efficiency. In this project, I will (1) survey existing approaches for classical and heuristic methods for irregular shape bin packing problems, (2) implement a prototype algorithm tailored to 3D printing contexts, and (3) evaluate its performance in terms of packing efficiency and runtime. Through this, the project seeks to connect the theoretical foundations of approximation algorithms with the real-world challenges of optimizing additive manufacturing workflows.

Related Work

In this section, we review existing literature on bin packing algorithms. We will first cover traditional regular bin packing algorithms, then we will focus on different Geometric Algorithms and Meta-heuristics for 2D irregular bin packing problems (Guo et al. 2022), which are most relevant to this project.

Traditional Bin Packing Algorithms

Linear Programming for 1D Bin Packing

Linear programming (LP) approaches formulate the packing problem as a set of linear inequalities and an objective function to be optimized. A common approach used is the Gilmore-Gomory method (Gilmore and Gomory 1961), which was first proposed for solving 1D bin packing problems. The state-of-the-art paper proved that the integrality gap is at most $O(\log(\text{OPT}))$ (Hoberg and Rothvoss, n.d.), and an open question is whether we can get a constant factor integrality gap for the Gilmore-Gomory LP. The log integrality is an improvement from the previous state-of-the-art by Karmarkar and Karp from the 80s (Karmarkar and Karp 1982), who proposed an algorithm that achieves an additive integrality gap of at most $O(\log^2(\text{OPT}))$ in polynomial time. Karmarkar-Karp algorithm is easier to understand than the log integrality algorithm, and serves as a good starting point for understanding LP-based packing algorithms. In the following section, we will briefly describe both the Gilmore-Gomory LP formulation and the Karmarkar-Karp algorithm for bin packing.

The Gilmore-Gomory LP for 1D Bin Packing: A simple LP might be to define a variable for each item and bin $x_{ij}$, which indicates the fraction of item i in bin j, and then minimize the total number of bins used. However, the LP might just be dividing each item into very small fractions and spreading them across many bins, more specifically, $\left\lceil\sum \text{item sizes} / \text{bin capacity}\right\rceil$ bins, which is a very loose lower bound and cannot be rounded to a good integral solution.

The Gilmore-Gomory LP (Gilmore and Gomory 1961) is a linear programming formulation for the 1D bin packing problem that solved the above problem. The core idea is to represent the packing patterns, instead of individual item placements. The objective function aims to minimize the total number of bins used.

$$\begin{align*} \text{Minimize } & 1^T x \\ \text{ s.t. } & Ax \geq n, x \geq 0 \end{align*}$$Where A is the pattern matrix, with each column representing a packing pattern and each row representing a unique item, the entry $A_{ij}$ indicates how many items i are included in pattern j. The variable x is a vector where each entry $x_j$ represents the number of times pattern j is used in the packing solution, and this can be fractional for the LP. $n$ is a vector where $n_i$ indicates the number of items of size i that need to be packed. The constraints $Ax \geq n$ ensure that the total number of items packed across all patterns meets or exceeds the required number of items for each size. We also have the non-negativity constraint $x \geq 0$, making sure that the number of times each pattern is used is non-negative.

Karmarkar-Karp Algorithm: Karmarkar-Karp algorithm (Karmarkar and Karp 1982) provides an efficient way to round the fractional solution obtained from the Gilmore-Gomory LP into an integral solution. There are different kinds of the Karmarkar-Karp algorithm; here we describe the additive integrality gap version, and it is described in the talk by Thomas Rothvoss, one of the authors of the integrality gap paper (Hoberg and Rothvoss, n.d.). This is a lecture he did in 2014 at the University of Washington, the recorded version is available on YouTube (Rothvoss 2014).

When constructing the LP, to prevent an infinite number of constraints/patterns, they first group items into same-sized groups, and all the items in the group are rounded up to the largest item in the group. This reduces the number of unique item sizes, and they proved that this step only adds an additive $O(\log(\text{OPT}))$ more bins to the solution.

After solving the LP, they use a rounding technique to convert the fractional solution into an integral one. The rounding process is just selecting the extreme points in the polytope defined by the LP constraints. They showed that this will round half of the fractional variables to integers in each iteration, and the number of iterations is at most $O(\log(\text{OPT}))$. Each iteration adds at most $O(\log(\text{OPT}))$ more bins, leading to a total additive integrality gap of $O(\log^2(\text{OPT}))$.

Billiard Algorithm for 2D Square Packing

Billiard algorithm is a heuristic method for 2D rectangular packing problems. The core idea is to allow rectangles to move freely within the bin, similar to billiard balls on a table. When a rectangle hits the boundary of the bin or another rectangle, it “bounces" off in a new direction. This process continues until no further movement is possible. Gensane and Ryckelynck (Gensane and Ryckelynck 2005) used this algorithm for packing 11, 29, and 37 congruent squares into the smallest possible square container.

Geometric Algorithms

Bottom-Left Algorithm

The Bottom-Left algorithm is a simple and widely used heuristic for 2D rectangular packing problems (Chazelle 1983). The algorithm works by placing each rectangle in the bottom-leftmost position available in the bin. For each rectangle, the algorithm scans the bin from the bottom-left corner to the top-right corner, looking for the first position where the rectangle can fit without overlapping with already placed rectangles. Once a valid position is found, the rectangle is placed there, and the algorithm moves on to the next rectangle. The Bottom-Left algorithm is easy to implement and runs in polynomial time; however, it does not guarantee an optimal solution, and the order of putting different sizes of rectangles can significantly affect the packing efficiency. Similarly, there are other variants like First-Fit, which places the rectangle in the first available position found during the scan, similar to Bottom-Left, but the scanning procedure can vary, and Best-Fit, which places the rectangle in the best available position, which is measured using the cost function defined based on specific situations.

Envelope Polygon

The envelope polygon method is one of the earlier approaches to tackle irregular shape packing problems (Adamowicz and Albano 1976). The core idea is to compute the convex hull (envelope polygon) that tightly bounds the irregular shape. By approximating the irregular shape with its envelope polygon, traditional packing algorithms designed for regular shapes can be applied. While this method simplifies the packing process, it leads to significant wasted space, especially for highly concave shapes.

No-Fit Polygon

The no-fit polygon (NFP) is a geometric construct used to determine feasible placements of one shape relative to another without overlap (Oliveira et al. 2000). Given two polygons A and B, the NFP of A with respect to B represents all the positions where A can be placed such that it touches but does not overlap B. The NFP is generated by “sliding" polygon A around polygon B and tracing the path of A’s reference point. This method is particularly useful in packing problems as it allows for efficient collision detection and placement validation. However, computing the NFP can be computationally intensive, especially because each shape can be rotated in multiple orientations, leading to a combinatorial explosion in the number of NFPs that need to be calculated (Guo et al. 2022).

Raster Methods

Raster methods involve discretizing the packing area into a grid of pixels or cells (Segenreich and Braga 1986). Each irregular shape is then represented as a set of occupied cells within this grid. During the packing process, the algorithm checks for overlaps by examining the occupied cells of the shapes being placed, which is much faster than traditional geometric methods. However, the accuracy of raster methods depends on the resolution of the grid. To achieve higher accuracy, a finer grid is required, which increases memory usage and computational overhead. If the grid is too big, it may lead to suboptimal packing solutions due to the loss of geometric detail.

Linear Programming

Linear programming (LP) and mixed-integer programming (MIP) were first used for 1D packing problem, later adopted to 2D irregular packing problems (Fischetti and Luzzi 2009). For 2D irregular packing, it is often combined with NFP to formulate constraints (Silva et al. 2010). It works well for most cases, but may struggle if the shape has too many vertices, resulting in the number of constraints becoming too large to solve efficiently (Guo et al. 2022).

Meta-heuristics Algorithms

Genetic Algorithms

Genetic algorithms are inspired by the process of natural selection and evolution (Goodman et al. 1994). They work by maintaining a population of candidate solutions, which evolve over generations through selection, crossover, and mutation operations. In the context of 2D irregular packing, one of the ways to represent a candidate solution is through the order of placing the shapes (Thomas and Chaudhari 2014). The algorithm will first start with randomly generated placement orders as candidates. In each generation, the algorithm will use these placement orders to pack the shapes using a deterministic packing algorithm, like Bottom-Left, then evaluate the score for each candidate based on packing density. Then, the algorithm will select the best-performing candidates as parents, and generate children, or new candidates, through crossover and mutation. An example of crossover is taking the first half of parent A’s placement order and the second half of parent B’s placement order to form a new placement order. Mutations can be done by randomly swapping the position of two shapes. Using this, the algorithm can generate the same number of candidates for the next generation and repeat until the improvement curve flattens, or the maximum number of generations is reached. Genetic algorithms are effective at exploring a wide solution space, and using the same philosophy of natural selection, they can converge towards high-quality solutions over time. However, how many candidates, how to select parents, and the rates of crossover and mutation are all important hyperparameters that need to be tuned for good performance.

Simulated Annealing

Simulated annealing is a probabilistic optimization technique inspired by the annealing process in metal forging (Mundim et al. 2018). It explores the solution space by iteratively making small random changes to the current solution. If a change leads to an improved solution, it is accepted. If it leads to a worse solution, it may still be accepted with a certain probability that decreases over time (controlled by the temperature parameter). This allows the algorithm to escape local minima and explore a broader solution space during earlier iterations, but only accept good moves and converge in later iterations. However, based on my own experience, the performance of annealing is highly dependent on the parameter settings. And due to the nature of randomness, annealing usually produces sub-optimal results for regular shapes. The optimal solution for regular shapes is always placing them in a grid-like manner, which is hard to reach with random processes.

Just like genetic algorithms, the cooling schedule (how fast we decrease the temperature after each iteration), initial temperature, and number of iterations are all important hyperparameters that need to be tuned for good performance. There are also tricks involved to improve the performance, for example, move in each iteration, but only rotate every few iterations (e.g., the iteration is divisible by 5), because rotation changes the configuration more drastically than moving. Another trick can be every 50 or 100 iterations, we force all shapes to move into the bin; this will help the algorithm converge faster.

Recent Research Directions

Most previous research on 2D irregular bin packing has focused on algorithms optimizing the position and orientation of each individual shape. However, from the recent survey (Guo et al. 2022), the authors suggested that recent research in 2D irregular bin packing could utilize physical simulation methods to achieve better results. The suggestion is to put all the shapes into the bin with random initial positions and orientations, then use physical simulation to let the shapes settle into a stable configuration. This approach leverages the free movement of shapes in physical simulation to explore the solution space more effectively. By allowing shapes to interact and settle naturally, the algorithm can potentially find more efficient packing arrangements that traditional methods might miss.

Shake and Greedy Insertion

A recent paper by Zhuang et. al. from 2024 (Zhuang et al. 2024) proposed a novel approach that combines rigid body physical simulation with a greedy insertion strategy. The algorithm starts by randomly placing all shapes within the bin and shaking them, giving them random kinetic energy and velocity. To obtain a higher packing density, the authors introduced a greedy insertion step during shaking. The idea is they start by adding a shrunken version of the shape into the bin, then enlarge it while shaking, this naturally pushes surrounding objects away, and the kinetic energy is pushed outwards so all the objects in the bin can accommodate the new shape and adjust to the best new configuration. This shaking and enlargement process is continued until the inserted shape reaches its original size, and the greedy insertion continues with the next shape until the bin cannot fit any new shapes. Although the focus of this paper is in 3D, but it provides inspiration towards using physical simulation for 2D packing problems.

3D Packing using Unreal Engine

Another interesting application I found is by Micronics, a 3D printer startup later acquired by Formlabs. They used the Unreal Engine, which is a popular game engine with a highly optimized physics engine. They utilized the built-in physics engine to simulate packing of 3D models into the build volume for SLS (Selective Laser Sintering) 3D printing (Micronics 2024). Because in SLS technology all parts will be printed in a powder cake, so model stacking on top of each other is allowed. The goal for packing is just to fit as many models as possible into the build chamber.

Their approach is similar to the previous algorithm, where user can drop models into the build chamber, and the physics engine will simulate the settling of the models. The user can then apply forces at specific points to shake the models and let them settle again. By utilizing the optimized fast physics engine in Unreal, the packing simulation can run in real-time, providing an interactive experience for users to optimize their packing layout. Although the problem is 3D packing instead of 2D, but it shows the potential of using physical simulation for packing problems in additive manufacturing.

Physical Simulation for 3D Packing in Chemical Engineering

Another interesting paper I found is in the chemical engineering field (Moghaddam et al. 2018). The authors proposed a rigid-body physical simulation approach to increase the packing efficiency of pellets in tubes for chemical processes. The algorithm can work for spheres, cylinders, and Raschig rings. The author then tested different ways of dropping the pellets into the tube, including dropping from the same position, random dropping positions, same orientation, or random orientation. The results actually show that dropping from the same location with the same orientation achieves the highest packing density, which is a little counterintuitive. This shows that physical simulation can be a powerful tool for real-world packing problems.

Implementation

In this section, I introduce my own implementation of a 2D irregular bin packing algorithm, which uses physical simulation to pack shapes.

Formal Problem Definition

Most previous research on 2D irregular bin packing has focused on packing a given set of shapes onto the plate. However, as we discussed in the introduction, in additive manufacturing applications, we often want to maximize the number of copies of a given shape that can fit into a fixed-size build plate.

Thus, the formal problem definition is as follows: for a given shape and a given rectangular build plate, duplicate as many copies as possible to propagate the whole build plate. For most 3D printing technologies, models can only be built for one layer, they cannot stack on each other, so we can reduce it to projecting the model to 2D, and pack it on a 2D build plate.

Intuition of the Physical Simulation Approach

The intuition is to put more objects in and delete from that. The core idea is to overestimate the number of objects that can fit in the build plate, then use physical simulation to let the objects settle into a stable configuration. Then we iteratively remove the objects with the most overlap area, shake, let it settle again, until there is no overlap. The implementation is done in Python, using the Pymunk physics simulation package (Blomqvist 2025).

Pseudo Code

The core idea of the algorithm is to start with an overestimated number of shapes, then use physical simulation to let the shapes settle into a stable configuration. If there are overlaps, we remove the shape with the most overlap area, then shake and let it settle again. This process continues until there are no overlaps. Then we return the final packed configuration.

- $N_{max} \gets$ over-estimated number of shapes that can fit in $W \times H$ with spacing $d$

- Initialize $P$ with $N_{max}$ random placements of $S$

- Simulate physics with gravity until settled

- Remove shapes $p$ from $P$ that are out of bounds

Results and Discussion

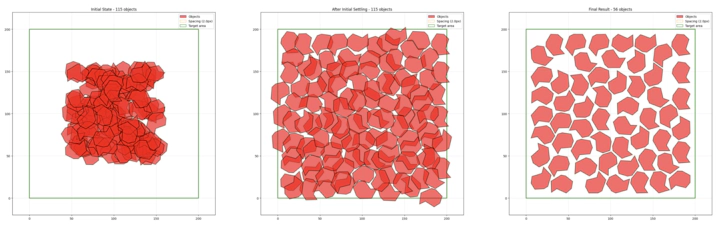

Below is an example of the packing result using the algorithm. The whole packing process takes 16 seconds to finish, and the final result packs 56 objects on the build plate, achieving a packing efficiency of 53.20% (measured by the total build plate area divided by the total area of the packed shapes plus spacing).

For the final result, there are definitely areas that are wasted. But being able to pack a whole plate with 56 objects in 16 seconds is decent performance, and we can trade a little packing efficiency for speed.

Below are more examples of packing results using this algorithm:

As we can see from the examples, the physical simulation-based algorithm works well for both irregular and regular shapes. For not too concave irregular shapes (left), the packing efficiency is decent, although there seems to be room for another one or two shapes.

For regular shapes like squares (middle), the algorithm is able to find a grid-like arrangement, achieving higher packing efficiency than the simulated annealing approach, showing that it is robust across regular and irregular shapes. On the top right corner, that square is rotated too much, causing the left column to have less space to pack a square, which makes the final packing result off by 1 square compared to OPT. Another limitation is that the physical engine runs slower when there are more objects to do collision checking, so the runtime is longer. This issue could be solved using a faster physics engine in C++ instead of Pymunk.

For highly concave shapes like the “C" shape on the right, the algorithm doesn’t perform as well as the packing quality of PreForm; it doesn’t find a very good “interlocking” placement. The reason could be due to the current shape removal strategy in my algorithm being naively deleting the object with the most overlap area, and doesn’t take into account if that shape forms a good configuration with certain surrounding shapes. A better shape removal strategy could be designed to improve the performance on highly concave shapes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this project surveyed various algorithms to solve the bin packing problem. We explored traditional LP-based algorithms for 1D bin packing, geometric algorithms like envelope, no-fit polygon and raster methods for irregular shapes, and meta-heuristics such as genetic algorithms and simulated annealing. We also explored new physical simulation based approaches. Each approach has its strengths and weaknesses, and but no single method is universally best for all packing scenarios, which is not robust enough for additive manufacturing applications.

In the implementation section, we presented a new approach based on physical simulation for 2D irregular bin packing. This method uses the principles of physical simulation and tendency of objects settlements to iteratively optimize the arrangement of objects, resulting in efficient packing configurations. The experimental results demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach, achieving competitive packing densities while maintaining reasonable computation times.

Future work could explore further refinements to the physical simulation method, such as improving the efficiency of the physical simulation engine for improving the speed, or experimenting with different object removal strategies to improve packing density for concave shapes.

References

Adamowicz, Michael, and Antonio Albano. 1976. “Nesting Two-Dimensional Shapes in Rectangular Modules.” Computer-Aided Design 8 (1): 27–33.

Blomqvist, Victor. 2025. Pymunk. Version 7.2.0. https://pymunk.org.

Chazelle. 1983. “The Bottomn-Left Bin-Packing Heuristic: An Efficient Implementation.” IEEE Transactions on Computers C-32 (8): 697–707. https://doi.org/10.1109/TC.1983.1676307.

Fischetti, Matteo, and Ivan Luzzi. 2009. “Mixed-Integer Programming Models for Nesting Problems.” Journal of Heuristics 15 (3): 201–26.

Gensane, Thierry, and Philippe Ryckelynck. 2005. “Improved Dense Packings of Congruent Squares in a Square.” Discrete Comput. Geom. (Berlin, Heidelberg) 34 (1): 97–109.

Gilmore, P. C., and R. E. Gomory. 1961. “A Linear Programming Approach to the Cutting-Stock Problem.” Operations Research 9 (6): 849–59. https://doi.org/10.1287/opre.9.6.849.

Goodman, Erik D, Alexander Y Tetelbaum, and Victor M Kureichik. 1994. “A Genetic Algorithm Approach to Compaction, Bin Packing, and Nesting Problems.” Case Center for Computer-Aided Engineering and Manufacturing. Michigan State University 940702.

Guo, Baosu, Yu Zhang, Jingwen Hu, et al. 2022. “Two-Dimensional Irregular Packing Problems: A Review.” Frontiers in Mechanical Engineering Volume 8 - 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmech.2022.966691.

Hoberg, Rebecca, and Thomas Rothvoss. n.d. “A Logarithmic Additive Integrality Gap for Bin Packing.” In Proceedings of the 2017 Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (SODA). https://doi.org/10.1137/1.9781611974782.172.

Karmarkar, Narendra, and Richard M. Karp. 1982. “An Efficient Approximation Scheme for the One-Dimensional Bin-Packing Problem.” 23rd Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (Sfcs 1982), 312–20. https://doi.org/10.1109/SFCS.1982.61.

Korte, Bernhard, and Jens Vygen. 2006. “Bin-Packing.” In Combinatorial Optimization: Theory and Algorithms, vol. 21. Algorithms and Combinatorics. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-29297-7_18.

Micronics. 2024. How We BUILT a 3D Printer That Can Print ANYTHING! YouTube.

Moghaddam, Elyas M., Esmail A. Foumeny, Andrzej I. Stankiewicz, and Johan T. Padding. 2018. “Rigid Body Dynamics Algorithm for Modeling Random Packing Structures of Nonspherical and Nonconvex Pellets.” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 57 (44): 14988–5007. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.8b03915.

Mundim, Leandro R, Marina Andretta, Maria Antónia Carravilla, and José Fernando Oliveira. 2018. “A General Heuristic for Two-Dimensional Nesting Problems with Limited-Size Containers.” International Journal of Production Research 56 (1-2): 709–32.

Munroe, Randall. 2023. Square Packing. Https://xkcd.com/2740/{.uri}.

Oliveira, José F, A Miguel Gomes, and J Soeiro Ferreira. 2000. “TOPOS–a New Constructive Algorithm for Nesting Problems: TOPOS–Ein Neues Konstruktionsverfahren für Das „Nesting-Problem”.” OR-Spektrum 22 (2): 263–84.

Rothvoss, Thomas. 2014. Better Algorithms for Bin Packing. YouTube video; UW Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wy45-JH8_yY.

Segenreich, Solly Andy, and Leda Maria P Faria Braga. 1986. “Optimal Nesting of General Plane Figures: A Monte Carlo Heuristical Approach.” Computers & Graphics 10 (3): 229–37.

Silva, Elsa, Filipe Alvelos, and JM Valério De Carvalho. 2010. “An Integer Programming Model for Two-and Three-Stage Two-Dimensional Cutting Stock Problems.” European Journal of Operational Research 205 (3): 699–708.

Thomas, Jaya, and Narendra S Chaudhari. 2014. “A New Metaheuristic Genetic-Based Placement Algorithm for 2D Strip Packing.” Journal of Industrial Engineering International 10 (1): 47.

Zhuang, Qiubing, Zhonggui Chen, Keyu He, Juan Cao, and Wenping Wang. 2024. “Dynamics Simulation-Based Packing of Irregular 3D Objects.” Comput. Graph. (USA) 123 (C). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cag.2024.103996.

Disclaimer

This project is entirely independent of my work at Formlabs or any other employer. All algorithms and implementations described here are my own work, developed solely for this course project. Any references to commercial software, features, or workflows are based on publicly available information or personal experience and do not disclose proprietary source code, internal methods, or confidential information. This content is intended for educational and research purposes only.