Titanium Color "Printing" Using Electrochemical Anodization

Table of Contents

Overview

This project is my Independent Undergraduate Honor Thesis, supervised by Prof. Emily Whiting. The goal of this project is to develop a pipeline that converts an user input image into GCode commands for a modified conventional 3D printer. The modified 3D printer is capable of electrochemically anodizing titanium to create color prints. The project is based on my previous group project on Titanium Color Printing using Laser during CS 581 Computational Fabrication course at Boston University.

Publication Link: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3774746.3779241

Project Link: Titanium Color Printing using Electrochemical Anodization

Publication News: Paper Accepted at SCF 2025

Abstract

We present a low-cost system that transforms user images into anodized titanium prints using a modified desktop FFF 3D printer. The pipeline integrates image processing, perceptual color mapping, and pixel-based anodization to reproduce multicolored images directly on titanium surfaces. In contrast to prior hobbyist methods that depend on manual and unsafe techniques, our approach automates the workflow from color mapping to G-code generation, providing a safer and more reliable process that can be easily replicated on other setups. This work shows how accessible digital fabrication tools can be adapted to broaden creative expression in metals and lower the barrier to advanced finishing techniques.

Authors:

- Ruichen Liu

- Emily Whiting

Introduction

Titanium anodization is an electrochemical process that generates vibrant colors via controlled oxide layer, useful for both decorative and functional applications (McClements 2022). It is widely used in biomedical implants for its surface properties (Wang et al. 2019; Sudha et al. 2022), and anodized TiO$_2$ nanotubes show promise for corrosion resistance and catalysis (Valeeva et al. 2018; Chatterjee et al. 2006). However, existing anodization systems are expensive and complex (Ye 2024), while low-cost alternatives are often unsafe (Ritter 2024; [goldscott] n.d.) or capable of only simple shapes (Liu et al. 2023), limiting broader adoption by artists and makers.

We present a fully automated pipeline that converts user images into multicolored titanium prints using a standard desktop FFF 3D printer, the first low-cost system to achieve full-image reproduction via anodization. Our pixel-based approach discretizes images into dots with controlled anodization times, avoiding the instability of speed-based methods and ensuring consistent color reproduction across setups. Images are scaled to 32 $\times$ 32 pixels to balance detail and fabrication time, with colors mapped to an experimentally derived titanium palette. By integrating image processing, color mapping, and G-code generation, our method makes titanium anodization safe, reliable, and accessible to makers.

Related Work:

Hobbyist anodization, such as drawing with a sponge soaked in conductive solution, can create colored patterns but is unsafe and hard to reproduce (Ritter 2024; [goldscott] n.d.). Liu et al. (2023) proposed a safer CNC-controlled method using a 2D plotter, though it is limited to simple shapes and requires an expensive programmable power supply. Jwad et al. (2016) used lasers for multi-color titanium anodization, but the setup is costly and hazardous due to high-power laser exposure.

Beyond anodization, prior work has explored connecting digital images to physical output in other media. Prévost et al. (2016) developed an interactive spray-painting system that reproduces murals with feedback and optimization. Panotopoulou et al. (2018) created a pipeline for watercolor-style printing from user images. These systems demonstrate how image processing can bridge user intent and fabrication outcomes.

We extend these ideas to metal surface finishing, introducing a safe, accessible pipeline for reproducible, multicolored image fabrication on titanium for the maker community.

Methods

3D Printer Modification:

We modified a Bambu Lab A1 mini by mounting a custom anodization tool on the toolhead using a 3D-printed holder modified from an open-source design (Infilament 2024). The tool consists of a soft-tipped pen wrapped with conductive wire, connected to a 0–110V DC manual power supply, and dipped in an over-concentrated sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) solution ([goldscott] n.d.). The wire ensures electrical contact while the soft tip delivers the electrolyte to the titanium surface.

Voltage–Color Relationship:

To determine the palette of colors producible by anodizing titanium, voltages from 5V to 65V were tested. Colors below 15V appeared too faint, while voltages above 65V posed safety risks.

Image Processing:

The image is scaled to 32 $\times$ 32 pixels, matching a 3 mm toolhead on a 100 by 100 mm titanium plate with 5 mm margins on each side. The image is then quantized using k-means. The quantized colors are then mapped to the titanium palette in the CIE Lab space (Carter et al. 2018) using the CIEDE2000 difference algorithm (Sharma et al. 2005) for perceptual accuracy.

G-code Generation:

The remapped image is converted into G-code, with voltages processed from low to high. For each voltage, the algorithm writes the x- and y-coordinates of matching pixels, inserting pauses between voltage changes so the user can adjust the power supply. Each dot is estimated to take 6s, providing progress indicators and triggers rinsing every 3 minutes to keep the toolhead moist and conductive.

User Interface:

Users upload images via a web interface, select palette colors (optional), preview results, estimate print time, view voltage instructions, and download G-code. Advanced users can refine results in a Jupyter notebook with segmentation, k-means clustering, and manual color edits.

Results and Conclusion

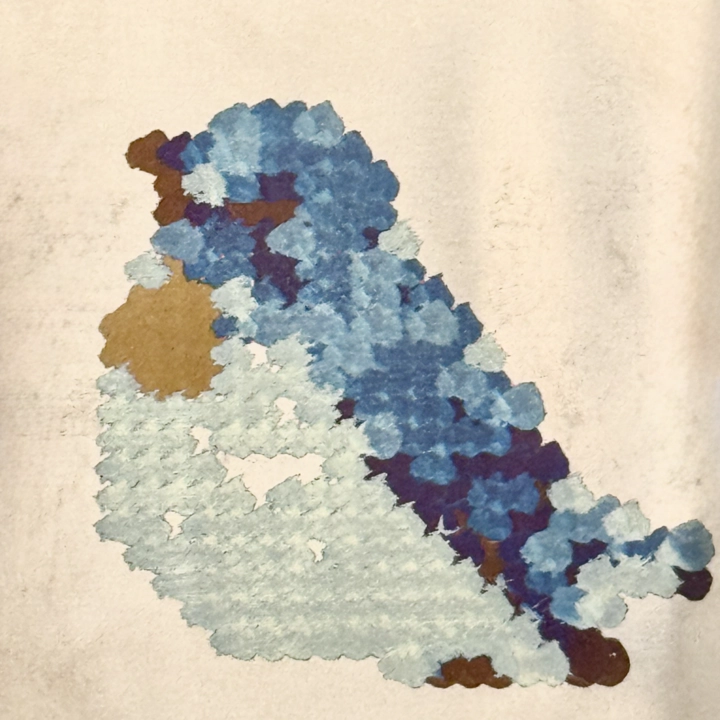

The pipeline fabricates colorful titanium prints with consistent colors. To keep objects recognizable at 32 $\times$ 32 resolution, we used pixel-style inputs for Figure 5. We tested various images (Figures 1 and 5), producing 4 results on 100 mm by 100 mm plates. Fabrication took 40 minutes for images (d) and (e) in Figure 5 (704 dots) and 102 minutes for (f) (1024 dots).

In conclusion, we demonstrate a fully automated pipeline that transforms user images into multicolored titanium prints on a standard desktop FFF 3D printer. By integrating image processing, perceptual color mapping, and G-code generation, our system makes titanium anodization accessible without specialized equipment. These results highlight how common 3D printers can be repurposed into safe and customizable metal-finishing platforms, lowering the barrier to creative applications of anodized titanium.

Demo Requirements

The demo uses 3 power outlets for the 3D printer, power supply, and laptop.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Qi Guo and Chenxi Yu for collaboration and Sam Silverman for guidance on the course project that inspired this work. We also acknowledge the Boston University Engineering Product Innovation Center for tool assistance and note that input images in the results were generated by DALL·E 3 (OpenAI 2024).

References

Carter, E. C., J. D. Schanda, R. Hirschler, et al. 2018. Colorimetry, 4th Edition. CIE 015:2018. CIE Technical Report. Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage (CIE). https://doi.org/10.25039/TR.015.2018.

Chatterjee, Subhasish, Miriam Ginzberg, and Bonnie Gersten. 2006. “Effect of Anodization Conditions on the Synthesis of TiO2 Nanopores.” MRS Proceedings 951. https://doi.org/10.1557/proc-0951-e09-27.

[goldscott]. n.d. Anodize Titanium! https://www.instructables.com/Anodize-Titanium/.

Infilament. 2024. [A1 (Mini) Pen Plotter Mod - No extra parts]. https://makerworld.com/en/models/590547.

Jwad, Tahseen, Sunan Deng, Haider Butt, and S. Dimov. 2016. “Laser Induced Single Spot Oxidation of Titanium.” Applied Surface Science 387: 617–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.06.136.

Liu, Ranger, Harpreet Singh Sareen, and Yasuaki Kakehi. 2023. “A CNC Approach to Anodized Titanium Drawing.” Proceedings of the 8th ACM Symposium on Computational Fabrication (New York, NY, USA), SCF ‘23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3623263.3629157.

McClements, Dean. 2022. Everything You Need to Know about Titanium Anodizing. https://www.xometry.com/resources/machining/titanium-anodizing/.

OpenAI. 2024. DALL·e 3. https://openai.com/index/dall-e-3/.

Panotopoulou, Athina, Sylvain Paris, and Emily Whiting. 2018. “Watercolor Woodblock Printing with Image Analysis.” Computer Graphics Forum (Proceedings of Eurographics) 37 (2): 275–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/cgf.13360.

Prévost, Romain, Alec Jacobson, Wojciech Jarosz, and Olga Sorkine-Hornung. 2016. “Large-Scale Painting of Photographs by Interactive Optimization.” Computers & Graphics 55: 108–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cag.2015.11.001.

Ritter, Chayton. 2024. Anodizing the iPhone 15 Pro. iFixit. https://www.ifixit.com/News/89241/anodizing-the-iphone-15-pro.

Sharma, Gaurav, Wencheng Wu, and Edul N. Dalal. 2005. “The CIEDE2000 Color-Difference Formula: Implementation Notes, Supplementary Test Data, and Mathematical Observations.” Color Research & Application 30 (1): 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/col.20070.

Sudha, D., R. Suganya, A. Revathi, K. Yoghaananthan, and V. Sivaprakash. 2022. “Anodization of TiO2 Nanotubes on Titanium Alloys and Their Analysis of Mechanical Properties.” Materials Science Forum 1070: 127–32. https://doi.org/10.4028/p-8r3ay6.

Valeeva, A. A., E. A. Kozlova, A. S. Vokhmintsev, et al. 2018. “Nonstoichiometric Titanium Dioxide Nanotubes with Enhanced Catalytical Activity Under Visible Light.” Scientific Reports 8 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28045-1.

Wang, Tingting, Lina Wang, Qianqian Lu, and Zhen Fan. 2019. “Changes in the Esthetic, Physical, and Biological Properties of a Titanium Alloy Abutment Treated by Anodic Oxidation.” J. Prosthet. Dent. 121 (1): 156–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2018.03.016.

Ye, Ronan. 2024. Titanium Anodizing: Process, Cost and Colors. 3ERP blog. https://www.3erp.com/blog/titanium-anodizing.